How to Learn Martian Charles Hockett Comment Review

Science is better with friends —

Andy Weir'due south Project Hail Mary and the soft, squishy scientific discipline of linguistic communication

A deep dive into xenolinguistics, pragmatics, the cooperative principle, and Noam Chomsky!

Enlarge / Artist's impression of either agreement existence achieved or intergalactic war being incited, I'chiliad not sure which.

Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

Andy Weir'due south latest, Projection Hail Mary, is a expert book that you lot'll most certainly bask if you enjoyed Weir'due south freshman novel The Martian. It's some other tale of solving problems with science, as a lone human named Ryland Grace and a lone alien named Rocky must save our stellar neighborhood from a star-eating parasite called "Astrophage."PHM is a buddy picture in space in a way that The Martian didn't become to be, and the interaction between Grace and Rocky is the biggest reason to read the volume. The pair makes a hell of a problem-solving team, jazz easily and fist bumps and all.

But the relative ease with which Grace and Rocky understand each other got me thinking virtually the existent-globe issues that might ascend when ii beings from vastly different evolutionary backgrounds try to communicate. PHM's otherwise solid commitment to scientific discipline leans a bit here on what nosotros might call the "anthropic principle of scientific discipline fiction," after the more than well-known general anthropic principle. To wit: Rocky and Grace tin can communicate well with each other because it serves the story, and if they couldn't, the book would be shorter and less interesting.

I get it—that's how storytelling works. I don't want to sound like a biting basement-dwelling critic throwing shade at a bestselling science fiction author. ButPHM is similar The Martian in that information technology'south well-nigh solving bug realistically. From my nerd basement throne, it feels like the softer sciences of linguistics and anthropology (or perhaps xenolinguistics and xenoanthropology) don't get the aforementioned phase time equally their more STEM-y counterparts like physics and relativity.

Indeed, Grace chop-chop builds a workable level of rapport with his conflicting counterpart:

I pull the jumpsuit on. I've decided today is the day. After a week of honing our language skills, Rocky and I are gear up to start having real conversations. I can fifty-fifty sympathise him without having to look at the translation about a third of the time at present.

The acquisition of a wholly conflicting language is treated similar a math problem—a series of steps that, if completed in the right order, guarantees comprehension. Our two intrepid interstellar explorers notice each other in the void and start cooperating. They link their ships and effigy out the pure mechanics of communication. Both apply sound, though Rocky communicates with chords and whistles. Grace has a laptop with a copy of Excel and some Fourier transform software, while Rocky has an eidetic retentiveness, so the physical layer of communication is easily handled. They quickly work out equivalent words for things around them, like "wall" and "star" and "Astrophage." They likewise knock out "yep" and "no" through some quick pantomime, followed by "good" (or at least "I appear to approve of this") and "bad" (or at least "I appear to disapprove of this").

Subsequently some more than linguistic communication learning, nosotros come up to this particular passage—the passage that pushed me over the edge into writing this piece:

Proper nouns are a headache. If you're learning High german from a guy named Hans, you just call him Hans. But I literally can't make the noises Rocky makes and vice-versa. So when 1 of us tells the other well-nigh a name, the other ane has to selection or invent a word to represent that name in their own language. Rocky'south actual name is a sequence of notes—he told it to me once but it has no meaning in his language, and then I stuck with "Rocky."

Merely my proper noun is really an English word. So Rocky simply calls me the Eridian word for "grace."

How, exactly, does one build the necessary cerebral scaffolding—in a period of time measured in weeks—to explicate "grace" to an alien that may or may not have the emotional wiring to even anticipate the word? And if the alien does have an equivalent word, how do you lot know with any corporeality of certainty that the word means the same thing? "Grace," after all, is a squishy concept involving morality and value judgments. A huge assortment of other concepts have to be settled with equivalencies before y'all can even begin to understand whether or not, when the conflicting says "grace," it means the aforementioned thing to each speaker.

All of which made me wonder whether the language learning portrayed in PHM was, well,realistic.

Caput games with foreigners

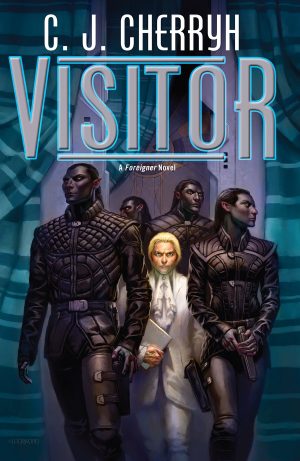

Sci-fi does offer us many other visions of alien communication. I'thousand no linguist, but I exercise read a lot—and one of my favorite authors is the inimitable C.J. Cherryh, arguably one of the last living thousand masters of scientific discipline fiction. Cherryh'southward specialty genre might best be described every bit "anthropological SF," due to her bookish grounding in archeology and mythology. She has a knack for writing conflicting characters that finely manage the rest between being interesting and also truly, believably alien—non just in course, but in motivation and emotion. And Cherryh's work, to pick on her equally an instance, posits a hell of a lot more than difficulty in communicating with aliens.

Though her body of work stretches back to the 1970s, Cherryh's knack for getting the conflicting/human interface right is shown off to bully consequence in her Foreigner series of novels, which features a lone homo translator living among an emotionally incompatible race of aliens called atevi. Atevi are superficially much like humans—a scrap taller, different skin color, but they're bilaterally symmetric humanoids with two artillery and two legs and a head. They wait more or less like us, and that'due south how the issues start.

Enlarge / C.J. Cherryh's atevi. Alpine, nighttime, and surprisingly alien in spite of their human-similar appearance.

Humans prove upward at the atevi home world accidentally, since information technology's the merely habitable refuge a failing and lost human colony ship can reach with the ship's remaining supplies. Although the atevi are barely past the steam age, the 2 peoples accept a peaceful and productive start contact. Things go really well for a few years—humans get-go to integrate into atevi society and freely share their technology.

So, suddenly, war breaks out. Neither side actually understands why. Shortly before the pocket-size human being population is annihilated, though, a ceasefire is reached. The two sides accept a footstep back to endeavour to figure out why they started fighting, and working the issues out for the reader takes most of the first book in the series.

The meridian-level reason, every bit it turns out, is that even though both races thought they were communicating with each other, the semantic equivalencies they built were completely misaligned—and one race'southward idea of "friendliness" was another race's idea of "pure lunatic insanity." Cherryh dwells on the idea that language is at least partially a product of phylogeny. When you and an alien use a discussion, your individual understanding of that discussion hinges on a whole host of factors that you share with others of your species, but you lot and an conflicting may not have such context in common at all. Both races, human and atevi, were acting logically from their ain signal of view—and both races, from the other's perspective, were responding to logical acts with apparent psychotic craziness.

Recollect of how much of man language and understanding is built on inherent, foundational concepts—our biology and base perceptions are part of the primal structures of language. If I every bit a human being am attempting to somehow talk with another human being with whom I have no linguistic communication in common, nosotros can still build certain assumptions into our attempts at communication. Even if I'm speaking to a member of an isolated or uncontacted culture, we both will have like underlying biological drives. If nosotros tin can figure out each other'southward give-and-take for "love," for example, I don't take to explain what love is. We both just know. Dig far enough down and we'll always detect some semantic bedrock on which to build a conversation.

Actual agreement isn't just a process of establishing equivalencies—it's a much more complex spider web of ferreting out the underlying concepts backside the words and checking how (or even if!) those concepts map to their counterpart concepts on the other side. Sometimes—often, in fact, with Cherryh'southward atevi—no useful correlation is possible. Atevi biology and development has produced fundamentally different emotional drives than human evolution produced. Atevi don't feel love or friendship; instead they have their ain emotional response based around hierarchical grouping. It's just every bit powerful and fulfilling as dearest and friendship—and it serves the same useful role of creating and enforcing cooperation and societal cohesion—but actually explaining what it feels similar in human terms is impossible. (At that place'south so much more to Cherryh's atevi, by the way. If you're in the mood for a cracking good read, I advise you grab the first book in the series and dig in!)

So which take on extraterrestrial language acquisition hews closest to reality?

I say potato, you say 🎶🎶🎶

Over again, I don't know. I'm merely a guy who writes about farts on the Internet. I needed to call in the large guns—bodily smart people with actual degrees in the talky sciences.

Dr. Betty Birner, professor of linguistics and cognitive science at Northern Illinois Academy.

Dr. Betty Birner is a professor of linguistics and cerebral science at Northern Illinois University. Dr. Birner's specialty is the field of pragmatics—which she summarized for me as the difference betwixt the words someone says and the intention behind those words. Pragmatics includes the study of how we as speakers of a language use inferences virtually intent—inferences sometimes congenital on inherent assumptions about context, which themselves can stem from biological underpinnings—to overcome language's ambiguities.

The question I put to her was this: going by our electric current understanding of how and why human languages operate, do we recall it would be applied—or even possible—for 2 divergently evolved sentient beings from different worlds to larn each other'southward languages well plenty in a curt amount of time (perhaps every bit trivial as a week) to usefully converse about abstruse concepts and to be reasonably assured that both beings really empathize those abstracts?

I asked Dr. Birner if she could aid me understand the commonalities that show up between man languages and what separates language (which requires construction) from advice (which is something most animals manage to do without language). It's a difficult subject to blast down, but Dr. Birner cited the work of Dr. Charles F. Hockett and pointed out that there are several broadly accepted criteria for what makes a language a linguistic communication. I of those criteria is the concept of syntax.

"Man languages all have syntax," she explained. "You take distinct pieces that y'all can put together in different orders to go unlike furnishings. Fifty-fifty sign languages take this. No fauna communicative system has information technology."

"How can I possibly ask an alien, 'What's your word for friendship?'"

Beyond syntax, another feature of linguistic communication is the concept of deportation. "I can talk about things," she said. "Distance, and time, and identify. Your domestic dog can't do that. Your canis familiaris can scratch at the door to communicate that she wants to become outside, but she'due south not going to be able to say she wanted to get outside yesterday."

Dr. Birner's ain specialty field of pragmatics has its own accept on what makes language, language: a thing chosen the cooperative principle. "The bones notion is that when we communicate we are cooperative in some very fundamental ways," she said. "We say the right amount. We say things that are relevant. We say things we at least believe to be truthful. So, we accept all these assumptions also about the other person being cooperative, and if we didn't believe they were trying to be cooperative in all of these ways, communication just couldn't work."

I pointed out that as a lay person, the most interesting function of this to me is how we selectively break the cooperative principle all the time—for humor, or for sarcasm, or whatsoever. Breaking the cooperative principle imparts its ain letters, and Dr. Birner agreed.

"Admittedly—that'due south function of the cool thing near the cooperative principle," she laughed. "Nosotros violate it! So there'southward a maxim of the cooperative principle that says, 'Say only what you believe to be true.' Well, we violate that all the time in metaphor. 'You are the low-cal of my life.' Well, no, yous're not a bunch of photons. Clearly this is fake. Merely you infer away about what I actually meant. So, yeah, how practice we know that anything that'south true of human being linguistic communication is true of an alien language?"

You gotta Noam when to agree 'em

Dr. Birner also (perchance inevitably) brought upwards Noam Chomsky, the world-famous linguist. He'due south responsible for, amid other things, the thought that some class of universal grammar exists in humans. We tin can speculate about whether or not Chomsky's theories are true for humans, but can we safely extend those theories to cover hypothetical sentient alien life that evolved in a completely different surroundings?

Enlarge / Linguist Noam Chomsky in 2018.

HEULER ANDREY / Getty Images

"He [Chomsky] has a notion," she said, "that there is an innate biological instinct for language in human beings—that linguistic communication is instinctive to me in the same way that spinning a web is instinctive to a spider. He almost single-handedly killed behaviorism dorsum in the fifties, because in behaviorism the notion was the child is born equally a bare slate, and Chomsky said that it would be absolutely impossible to acquire something every bit complex as human linguistic communication if yous are really a blank slate."

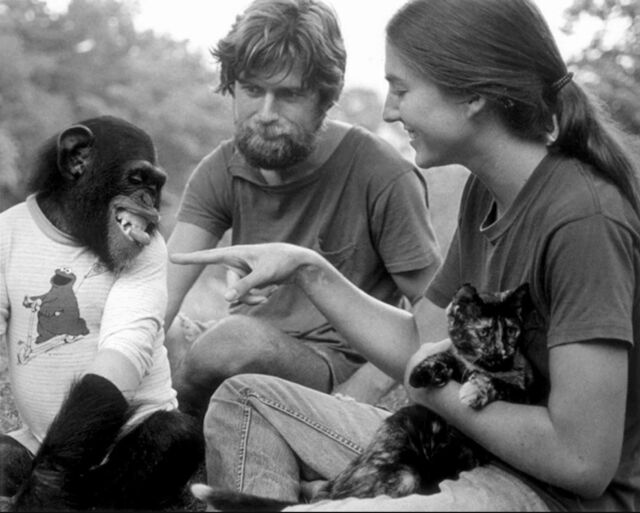

This was starting to sound a piddling familiar from previous Wikipedia trips. "There was, like, a monkey experiment built in hither at some point, isn't there?" I asked.

"Yeah, and people have done that," she responded. "They've raised chimps in their homes as though they were their own children, and the chimps do not larn linguistic communication—yet, a kid will soak information technology up effortlessly. And so, Chomsky has this notion that there is an innate 'universal grammar' that tells a human being infant what is and is not a possible man language. Yous tin see where this fits in with the notion of an alien language, because presumably an alien wouldn't have the same kind of universal grammar."

"Y'all would presume—I estimate you would assume—I don't know, we can make the rules be any nosotros want," I replied. "Merely you would presume that for an alien to evolve into roughly analogous sentience with a person, there would exist something equivalent to that."

I was feeling a little over my head, just I plowed on. "Would yous presume that?"

Enlarge / Nim Chimpsky and 2 of his man instructors in this still image from the HBO documentary Project Nim.

"I would assume things like symbolism—the symbolic nature of language," Dr. Birner replied. "There were a lot of people who assumed that that was one of the great cerebral leaps that made human linguistic communication possible—the notion that we can represent one matter as something else, and that's what language is." We represent things in the earth with words, and in one case you know that words represent concrete things, it's a short jump to realizing that words can represent abstract things, too.

Symbolic representation isn't necessarily straightforward, either. "A philosopher named Quine had this notion," she said. "If y'all're out in the field with somebody, and they point and say 'Gavagai!' and you look and you see a rabbit running through the field, y'all assume that gavagai in their language means rabbit. But how practice yous know it doesn't mean 'brownish,' or 'tail,' or 'leg,' or 'fur'—"

"Or, 'Wait at that!'" I said.

"Yeah, all of this other stuff is present, but we accept this whole object notion," she said. "Nosotros have a notion of what constitutes a distinct object, and nosotros assume that the word corresponds to that whole object as a default. Would the alien have that notion?"

"So," she continued, "I think you're request exactly the right question when you're asking non just how could nosotros inquire nearly an abstruse notion. There's i level, which is, 'How can I perhaps enquire an conflicting, what's your give-and-take for friendship?' But do they even take a concept of friendship, and how could you lot ask about that?"

Source: https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2021/05/andy-weirs-project-hail-mary-and-the-soft-squishy-science-of-language/

0 Response to "How to Learn Martian Charles Hockett Comment Review"

Post a Comment